Although I called this blog

"Springtails of Leicestershire and Rutland" that's only because it's a better title (in my opinion!) than

"Springtails, Bristletails and various other soil arthropods I come across while I'm looking for Springtails in Leicestershire and Rutland". However, it is also my intention to work on the massively-neglected bristletails, and I've been putting some effort into this over the last month. This post is very much an introduction and a summary of what I have learned.

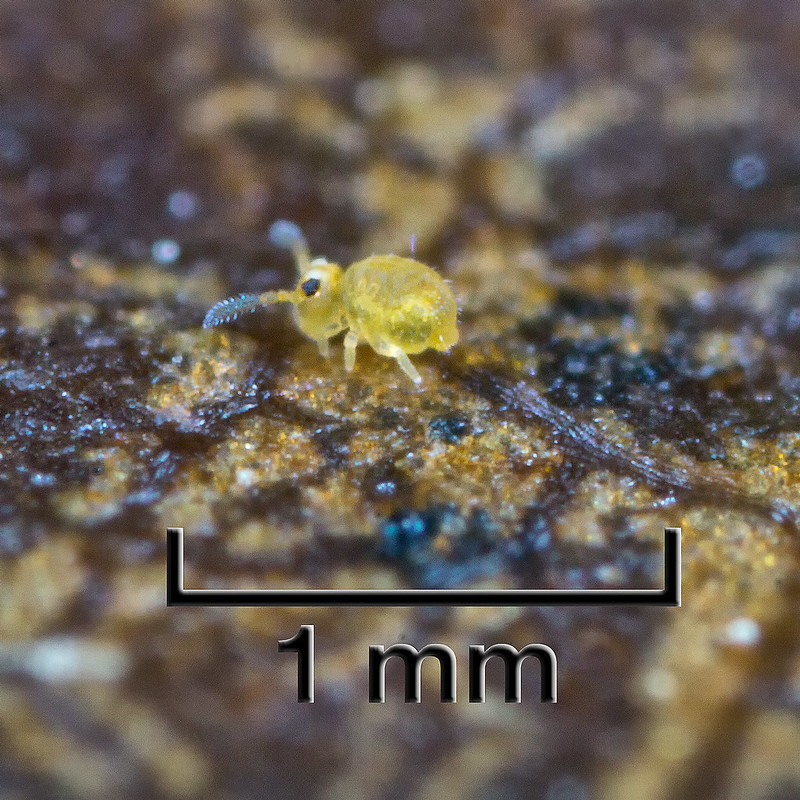

Bristletails (or Archaeognatha) are the most primitive of living insects, having existed since the mid-Devonian period. These cryptic, semi-cylindrical organisms are nocturnal and typically hide in crevices during the day, or are soil organisms living in the dark without eyes. About 500 species are known worldwide and they live in diverse habitats, from the sea shore to high altitudes in the Himalayas. Bristletails are herbivores and detritivores (detritus feeders). While they are not predatory, some species will scavenge the remains of arthropods. Some species of Symphyla can be agricultural pests, multiplying to high numbers and feeding on the roots of plants. Edwards quote densities of 88 million per acre (= 21,000 per square metre) in agricultural land (Edwards, C.A. (1958) The ecology of Symphyla. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 1(4), 308-319). The highest densities occur in light, humus-rich soils with significantly lower abundance in heavy clays (like Leicestershire!). The Symphyla are seasonal, with the highest numbers occurring in spring and autumn (related to soil temperature and moisture), although apparent numbers are affected by seasonal vertical migration in the soil (less so on clays where they tend to be restricted to the surface).

Phylum Arthropoda

Subphylum Hexapoda (from the Greek for six legs):

Class Insecta:

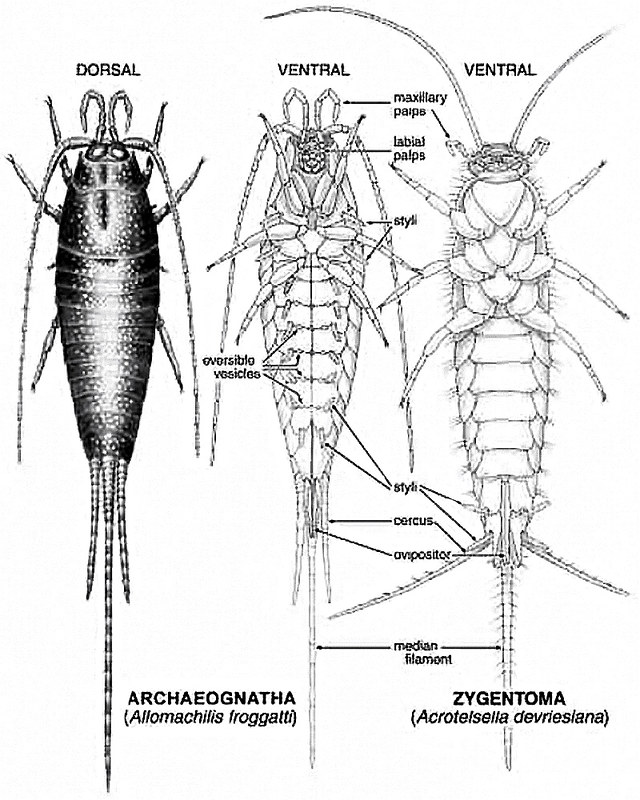

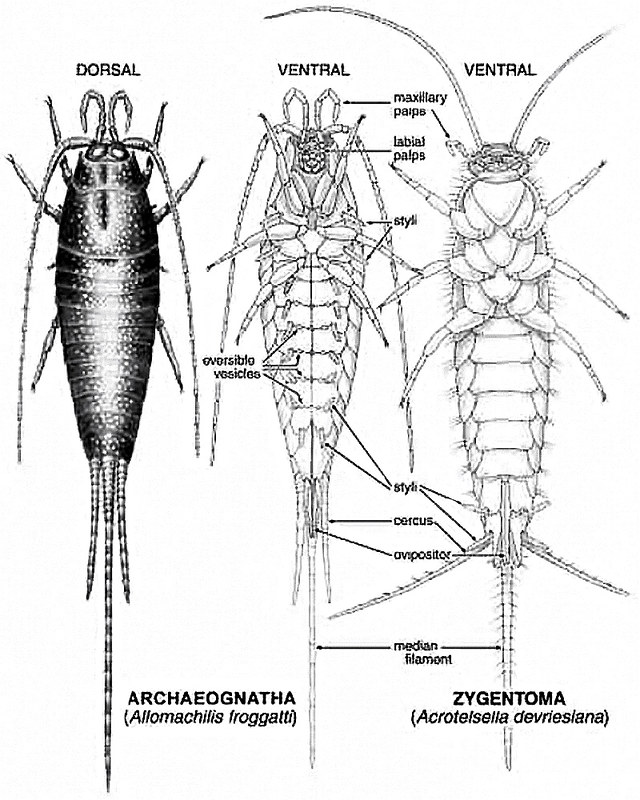

Order Zygentoma (formerly Thysanura) — silverfish and bristletails

Order Archaeognatha

Class Entognatha:

Order Diplura — "two-pronged bristletails" (Symphyla)

Bristletails are in the Orders Zygentoma (formerly Thysanura), the silverfish and firebrats; and Archaeognatha.

Etymology: Thysanura comes from the Greek thysano, which means fringed or bristled, and ura, which means tail. Thysanura, therefore, means "bristled tail," which is a reference to the caudal filaments characteristic of these organisms. Zygentoma comes from the Greek zygon, which means bridge. This refers to the unfounded idea that this group of insects is an evolutionary link (a bridge) between other orders of insects, particularly the insects.

Image source:

https://www.phrygane.tk/early-cretaceous/earliestlnsects.html

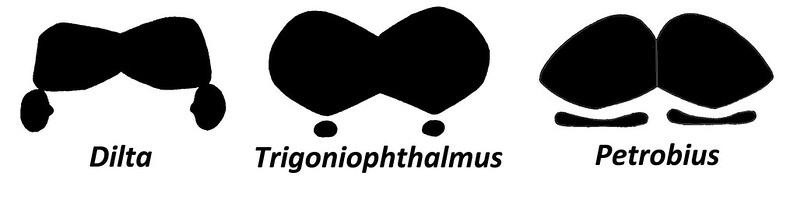

So what's the problem - why is this group so neglected in terms of biological recording? There are two problems. First, the occurrence of bristletails is quite uneven, with high numbers in some locations and very low numbers in others. This is in contrast to springtails, which are much more evenly distributed. Delving deep into the literature, more than one PhD project appears to have fizzled due to the problem of finding enough specimens to do anything useful with. Edwards laments the fact that the taxonomy of this group has been buggered up by so many taxonomic descriptions being based on single (misidentified) specimens! However, there's a worse problem - identification to species level. Most bristletails are relatively easy to get to genus level, but that's where the problem starts. Identification of Zygentoma is based on adult male specimens - females and juveniles cannot be identified to species level. And then you learn that some species hybridise extensively with others and at least some populations if not species are parthenogenetic (no males!) ... (Dejaco, T. et al (2016) Taxonomist’s nightmare... evolutionist’s delight: an integrative approach resolves species limits in jumping bristletails despite widespread hybridization and parthenogenesis. Systematic biology, 65(6), 947-974). The Diplura present a different challenge. Here some taxonomies have been based on morphological characters, including the number of segments, length of antennae, etc, but this changes as they mature. Symphyla hatch with 6 legs and relatively short antennae but pairs of legs and antennal segments are added with each moult. Identification can therefore only be achieved with adults, so the first stage with these organisms is always to count the number of legs!

Overall then, quite a challenge, and I can see why many people have shied away from this group. What a bunch of wimps!

;-)

Literature used:

Delaney, M.J. (1954) Handbooks for the Identification of British Insects. Vol. I, Part 2. Thysanura and Diplura. Royal Entomological Society, London.

Available for download from the R.E.S. website. A useful guide at least to genus level but somewhat superseded by the Work of Edwards.

Revised provisional key, based on Delaney, is available online courtesy of www.bristletail.net:

http://www.bristletail.net/british_isles/id/id.html

Edwards, C.A. (1959) Keys to the genera of the Symphyla. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 44(296), 164-169.

A useful overview to the genera, well illustrated and relatively accessible.

Edwards, C.A. (1959) A revision of the British Symphyla. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 132: 403-439.

The most detailed guide to the Symphyla, but not for the faint-hearted :-)