"Everything is everywhere but the environment selects"

"Everything is everywhere but the environment selects"

Early in the twentieth century the Dutch microbiologists Beijerinck and Becking proposed the hypothesis that

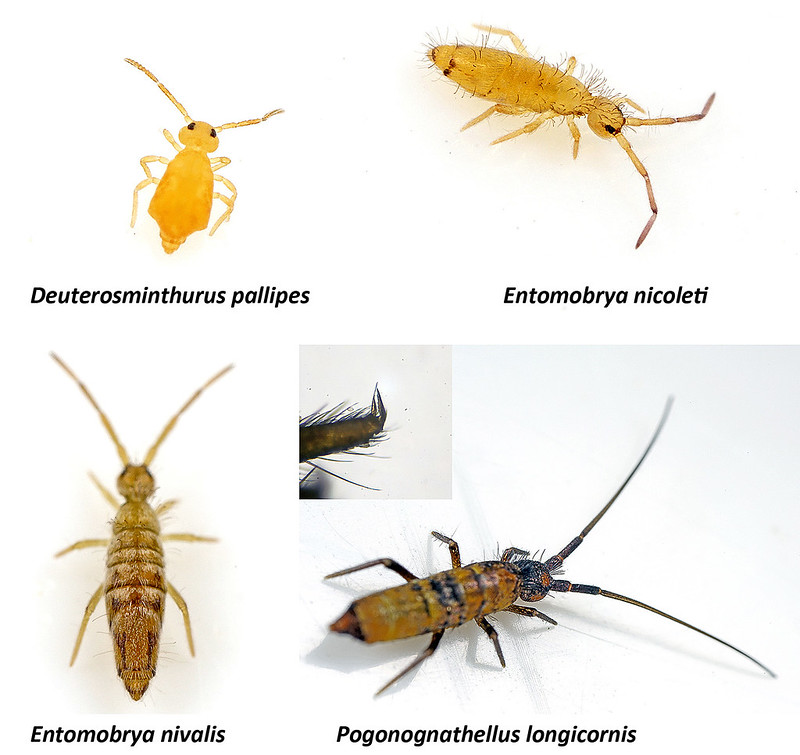

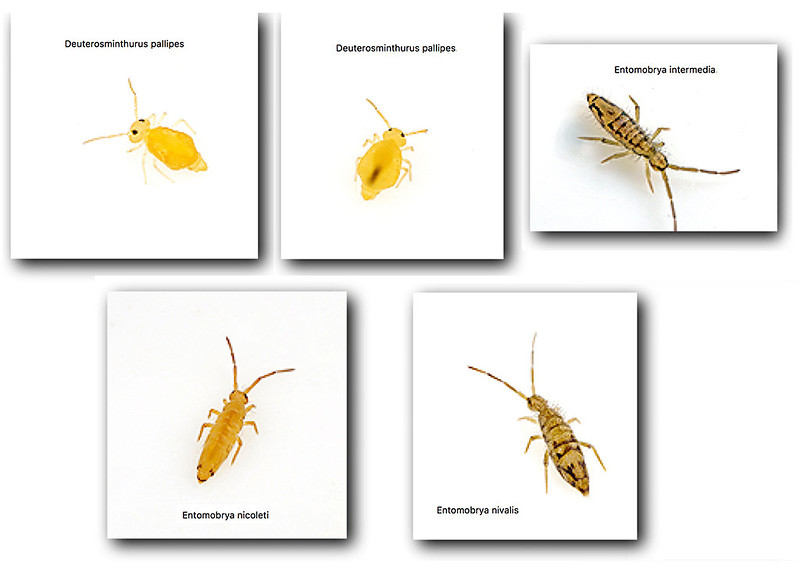

"Everything is everywhere but the environment selects" to explain the distribution of microorganisms. This has been much debated but it makes a lot of sense for highly mobile organisms that can be blown on the wind. At what scale it stops being true is unclear, but ecological determinism means that for all species, the environment selects which species persist. One of the most important factors in selection is climate, which determines the current distribution of species and will determine how these change in the future. The flora and fauna of Britain bear the signs of restriction by and subsequent repopulation following the last ice age. Not much survived under the ice cap but there were geothermal islands and not all of the UK was glaciated. The inability of springtails to fly limits their spread and repopulation when the ice retreats but their small size and abundance means that they are able to persist in suitable niches in otherwise adverse environments. Thus the present day distribution of springtails carries the historical signature of climate change. A recent paper examines two genera of springtails,

Entomobrya and

Lepidocyrtus, and reveals not only the impact of glaciation but also present day relationships (Faria, Shaw & Emerson, 2019).

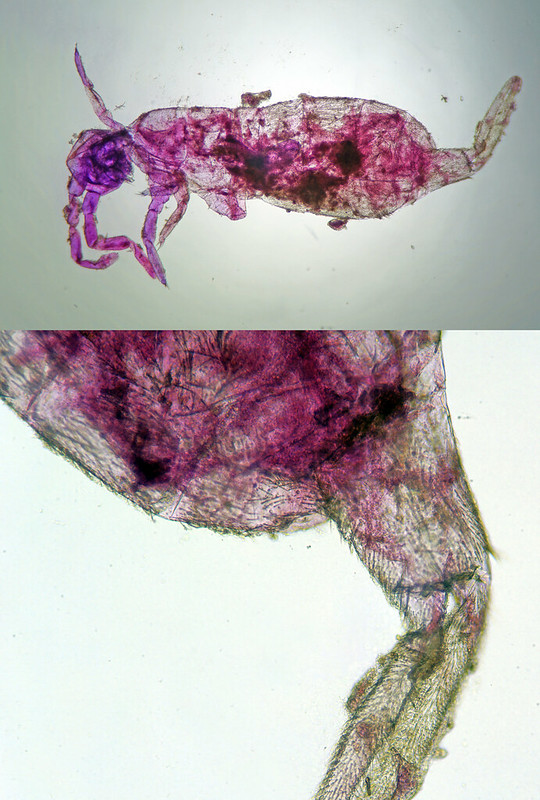

Springtail samples were collected from 98 sites across Britain and the DNA sequence of a region of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I gene determined and used to establish relationships. The patterns revealed indicate both geographical and genetic relationships in these two genera. Analaysis identified 12 Operational Taxonomic Units (genetic groupings) for

Entomobrya and 18 for

Lepidocyrtus in Great Britain.

Lepidocyrtus richness was significantly lower in glaciated than unglaciated areas, whereas there was no difference for

Entomobrya richness. The data reveal evidence for population persistence of Entomobrya (some of our most familiar springtails) OTUs within Great Britain, estimated to extend back at least some 77,000 years.

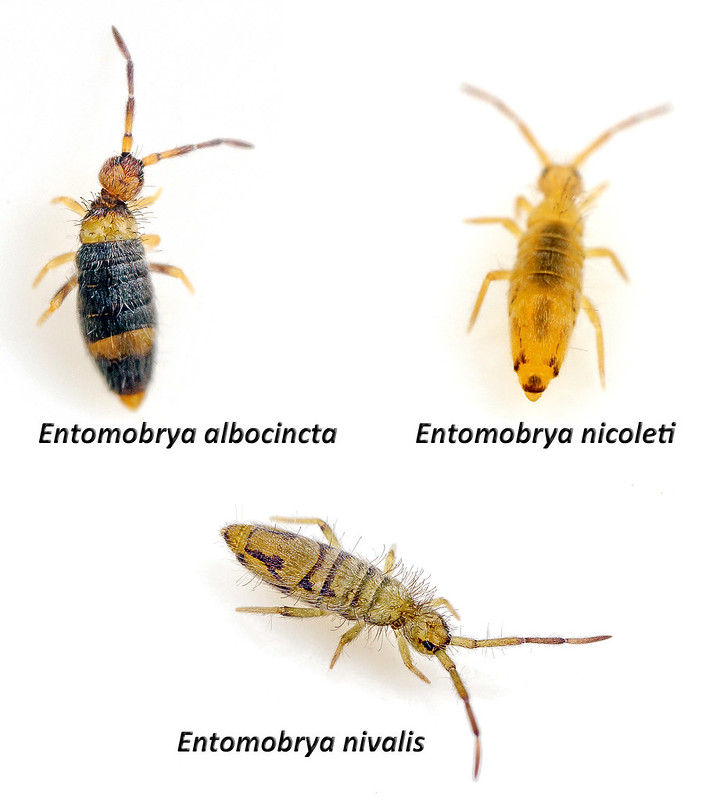

For me however, the most interesting aspect of this paper is what it says about present day species. For the most part, the recognised UK

Entomobrya species (

albocincta, intermedia, marginata, multifasciata, nicoleti, nivalis) behave themselves - colour‐pattern morphospecies were generally monophyletic but concealed two or more mtDNA OTUs. However, the correspondence between morphospecies and OTU was less clear for UK

Lepidocyrtus species (

curvicollis, cyaneus, lanuginosus, lignorum, ruber, violaceus) - 6 morphospecies harbour 18 distinct OTUs. Specimens assigned to the morphospecies

Lepidocyrtus cyaneus featured in seven OTUs, and the dominant OTU contained a mix of morphospecies (mainly

L. lignorum and

L. lanuginosus). Unexpectedly high cryptic species diversity has been noted previously in this genus and together these results suggest that key taxonomic features (mainly distribution of scales, ground colour) may be unreliable indicators of species boundaries. How exactly the genetic diversity of UK

Lepidocyrtus species translates into physical variability is unclear, but may go some way to explain the length of time I often spend scratching my head when examining

Lepidocyrtus specimens...

In response to my enquires, Frans Janssens commented:

Do not confuse OTU's with species. A species *can* map to several OTU's. ... The fact that "the dominant OTU contained a mix of morphospecies (mainly L. lignorum and L. lanuginosus)" suggests errors have been made in species identification of the specimens, given both species are easily distinguished based on morphology. Example: the specimens IDed as lanuginosus possibly were lignorum specimens with aberration in scale position on legs: such as specimens that lost all scales on legs during specimen handling. Please continue to record Lepidocyrtus based on morphology.

Matthew Shepherd also left an interesting comment:

"It's not just Lepidocyrtus - many soil animals, especially those with parthenogenesis (females giving birth to more clone females without fertilisation), don't really fit into the concept of a species... One of our commonest mites worldwide, Platynothrus peltifer, has been shown by Alfried Vogler and co-workers to have evolved into 12 global clades whose genes suggest that this species has been reproducing in this way, producing morphologically identical creatures, since the death of the dinosaurs. A 60 million year old species that is effectively actually just one cloned individual! I think that we can still learn a lot from lumping these morpho-types together for recording purposes, whether they're clusters of radiating species or ancient clones. It's still valid and ecologically useful to record brambles, dandelions and eyebrights, even though these are radiating aggregations of species. I think that we will have to just be a bit flexible with the data when we come to analyse it."

Using two genera of springtail,

Lepidocyrtus and

Entomobrya (Collembola), we test for genetic signatures of Pleistocene persistence of soil arthropods in Great Britain. A region of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (COI) gene was sequenced for 1,150 Collembola specimens from the genera

Lepidocyrtus and

Entomobrya across Great Britain. Individuals were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), and both OTU richness and geographical patterns of genetic variation within OTUs were compared between glaciated and unglaciated areas to identify signatures of OTU persistence through Pleistocene glacial events. Our analyses identified 12

Entomobrya and 18

Lepidocyrtus OTUs in Great Britain.

Lepidocyrtus OTU richness was significantly lower in glaciated than unglaciated areas, whereas there was no difference for

Entomobrya OTU richness. However, both genera presented clear patterns of geographically disjunct genetic variation and geographically localized diversification of OTUs. Estimated dates for the onset of in situ diversification events indicate population persistence that pre‐dates the Last Glacial Maximum. Patterns of genetic diversity within Collembola OTUs in Great Britain add to a growing body of evidence that elements of the invertebrate fauna have persisted in situ through Pleistocene glacial cycles. Genetic signatures of population persistence in more northern glaciated areas of Great Britain support a hypothesis of geothermal glacial refugia that call for further investigation with other soil mesofaunal taxa.