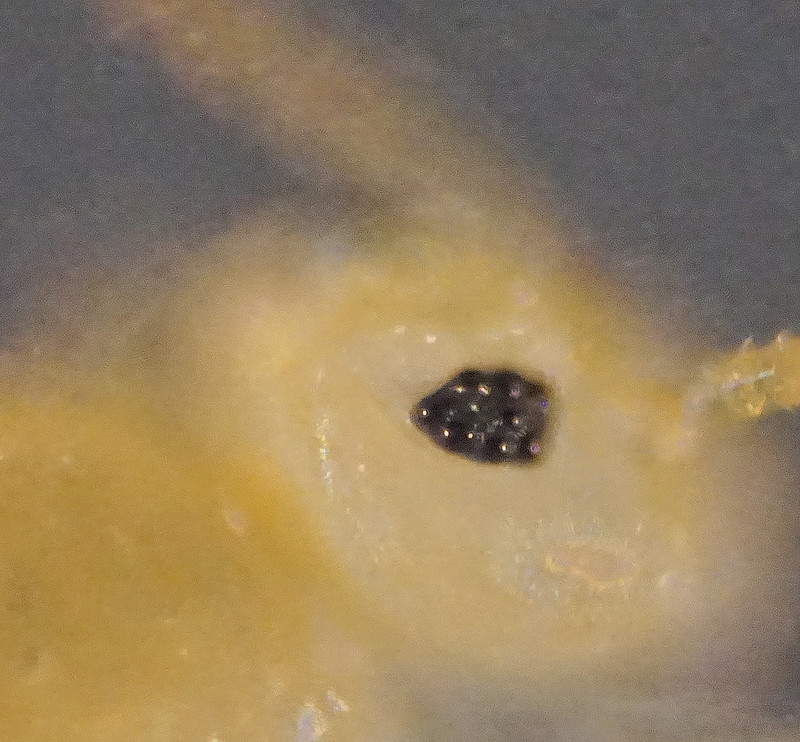

The collophore is the tube-like structure on the ventral side of the first abdominal segment of the body of springtails - it's what gives this group their name. Interestingly enough, although there are springtails without springs, as far as I'm aware there are no springtails without a collophore.

The collophore is used for in osmoregulation - water intake and excretion. In addition, the tip of the collophore carries mechano- and chemoreceptors which allow the animal to sense its environment. The collophore is actually a tubular pouch usually terminating in a bilobed vesicle, hence when fully extended the tip is forked (it is derived from a modified pair of abdominal appendages). At rest the collophore is contained within the body of the springtail but by contracting muscles and exerting hydrostatic pressure on the vesicle the springtail can evert the tube in order to drink. The collophore also works in opposition to the furcula (the spring) and can be used to control the direction in which the animal jumps (Favret, C., Tzaud, M., Erbe, E.F., Bauchan, G.R., & Ochoa, R. (2015) An Adhesive Collophore May Help Direct the Springtail Jump. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 108(5), 814-819). In at least some globular springtails the long prehensile vesicles are coated with an adhesive substance that permits the springtail to right itself when on its back.